How Doug Chiang's Team Designed The "Mandalorian" Universe and Figured Out How Slave I Actually Works

Art and design have been instrumental to Star Wars’ success since Ralph McQuarrie’s original paintings convinced studio heads at 20th Century Fox to give George Lucas’ ambitious space opera the greenlight. Doug Chiang, production designer on “The Mandalorian” and “The Book of Boba Fett,” as well as Lucasfilm’s vice president and executive creative director, has continued McQuarrie’s legacy of incredible design since he was chosen by Lucas himself to head the Lucasfilm Art Department for Episodes I and II.

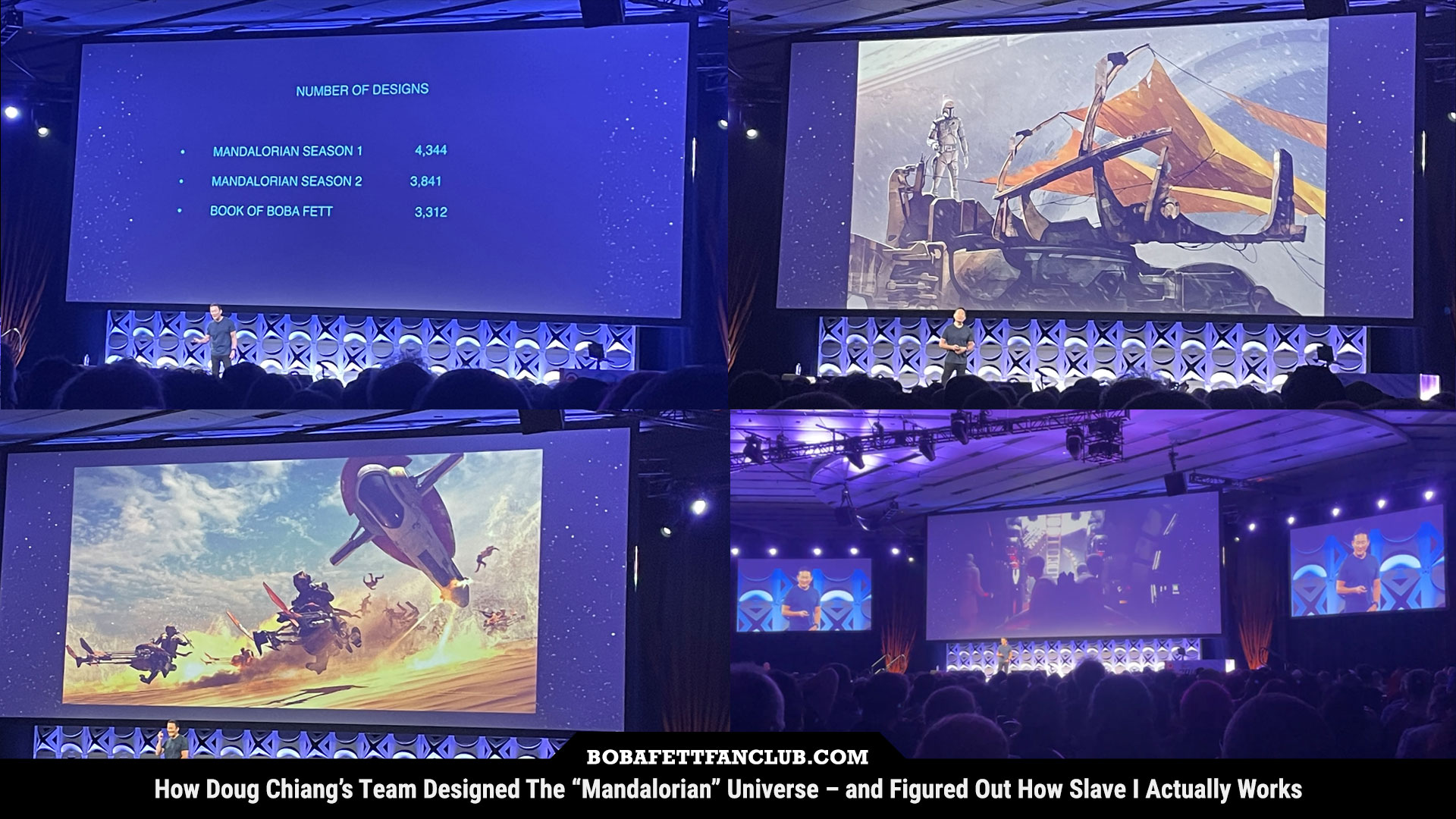

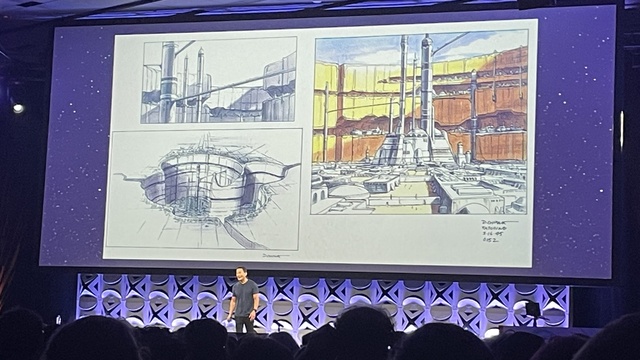

At Star Wars Celebration 2022 on May 28, Chiang gave a fascinating talk called “Designing The Mandalorian” in which he spoke about the challenges–and fun–of creating the worlds of both “The Mandalorian” and “The Book of Boba Fett” — and figuring out how Slave I would work. (The panel is also shown in the official Day 3 livestream starting at five hours and three minutes in.)

Chiang said that to create the first live-action Star Wars TV series, he and his team wanted to build a “cohesive universe” that combined the aesthetics of the prequels and original trilogies with a nod toward the artists and designers who started it all.

“In designing ‘The Mandalorian,’ we wanted to capture that essence that Ralph [McQuarrie] did so well. And from Joe Johnston [concept artist, effects technician and art director for the original trilogy and co-creator of Boba Fett’s design], we wanted to capture his iconic designs, his simple, memorable designs. They’re classic Star Wars designs.”

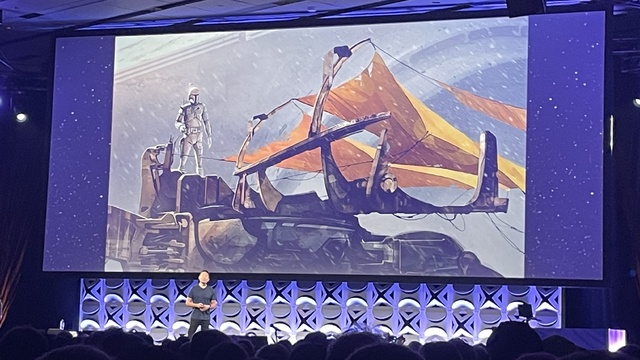

In fact, one of the first paintings Chiang created for “The Mandalorian” was inspired by Ralph McQuarrie’s original Boba Fett concept art.

“Star Wars design in many ways is like archaeology,” Chiang said. “You’re digging into the past to uncover ideas and make them your own.”

In fact, Chiang’s past work with Lucas on the prequel trilogy had a great influence on his design philosophy and process for “The Mandalorian” years later.

“We followed the guidelines set by George. Keep it simple. Design something a child could draw. Design for the silhouette, design for the iconic logo,” Chiang said.

Chiang added that working with Jon Favreau, writer and executive producer of “The Mandalorian,” even mirrored what it was like working with Lucas in a collaborative process in which concept art influenced the scripts and vice versa.

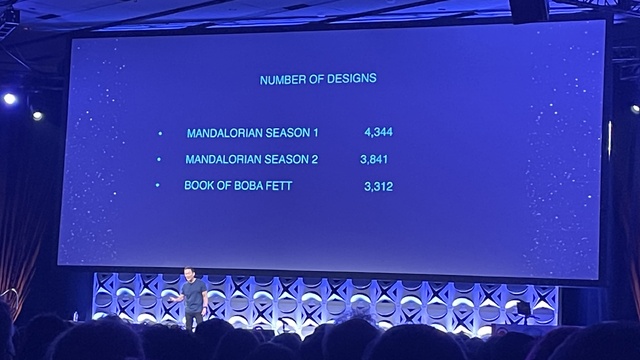

But the design team faced a monumental task when it came to the series set in “The Mandalorian” universe: designing two-and-a-half feature films worth of content each season with “half the budget and a third the time.”

New technology and design workflows made the ambitious project possible, according to Chiang. Virtual reality allowed the crew to scout sets virtually and make design decisions long before any physical set construction began.

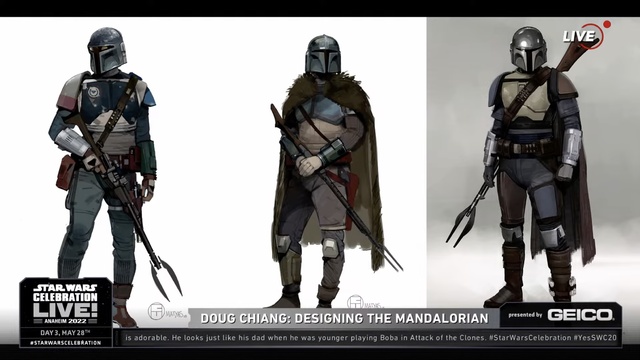

Another challenge the team faced was making Din Djarin distinct from the other Mandalorians viewers had previously seen in live action, Jango Fett and Boba Fett.

“To the casual fan, our Mando could easily be mistaken for a Boba because the details are very similar,” Chiang said. “So we focused on changing the silhouette to differentiate them.”

They did so by giving Mando a longer cape along with a pulse rifle that called back to the weapon Boba Fett first used in the 1978 Star Wars Holiday Special. Chiang noted that placing the rifle at a specific angle also helped distinguish the new character’s silhouette.

That strategy paid off and helped make Din Djarin a character fans loved. And after two seasons of designing for “The Mandalorian,” Chiang and his team set to work on “The Book of Boba Fett.”

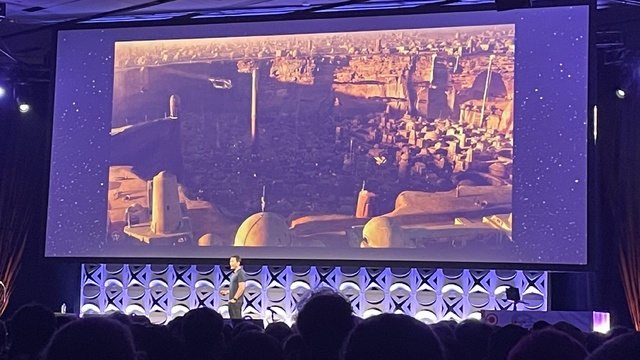

In another nod to the past, Favreau wanted this series to return to spaceport city in “The Phantom Menace,” Mos Espa. Some of Chiang’s concept art of the sunken city was never used in the films, despite being approved by Lucas. “The Book of Boba Fett” was the perfect opportunity to reveal those designs to the public for the first time.

“And the great thing about putting the city in a sinkhole is that it completely changed the horizon and gave it a new, distinct look that’s very different from Mos Eisley, even though all the architecture is pretty much the same,” Chiang added.

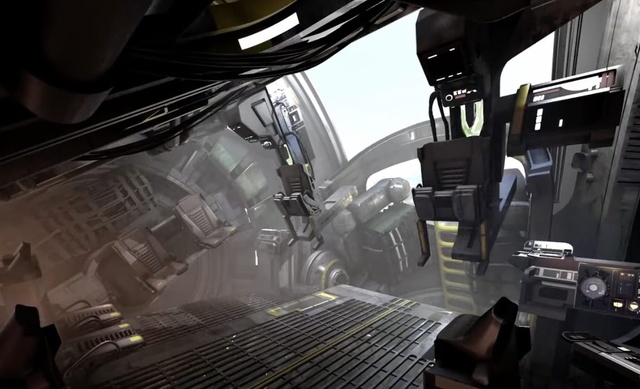

Another design challenge the team faced was figuring out how Slave I, which Chiang called an “all-time classic” Star Wars vehicle, would actually work on the inside as it rotated from horizontal to vertical flight. A partial cockpit was the only part of Slave I that was actually built for Attack of the Clones. That iteration of Slave I’s cockpit pivoted on metal arms to remain upright like a self-righting gimbal. But The Book of Boba Fett team had to conceptualize what happens in the rest of the ship as it rotates.

Unfortunately, having the cockpit itself rotate while the rest of the ship remained stationary was a bit too convoluted of an idea, so they decided to take the opposite approach: In the Book of Boba Fett, the cockpit remains fixed in one position while the main cargo hold rotates around it.

The panel also showed an animatic — first seen in the Disney Gallery The Mandalorian “Making of Season 2” on Disney+ — illustrating how Slave I’s cockpit remains stationery while the rest of the ship rotated around it.

It would have been difficult — not to mention expensive — to make this feat of engineering happen practically, so after building the floor, seats and some of the controls, ILM’s Stagecraft technology helped fill in the blanks by rendering the rest of the ship virtually in real time during filming.

“This is one of those great examples where our new technology is actually making this a very reasonable set for very low cost but powerful visual impact,” Chiang said.

In the final scene of “The Book of Boba Fett,” the daimyo sets his rancor loose in Mos Espa to defeat the Pykes’ giant Scorpenek droids. Chiang said Favreau charged the design team with exploring this idea during some of the first weeks of the show’s production. How do you figure out what that would look like? You look to monster movie classics like Godzilla and King Kong.

“Jon and Dave [Filoni, executive producer and writer of ‘The Book of Boba Fett’] gave us complete license to explore our wildest ideas, and it was our job to push it as far as we could. And not surprisingly, Jon would always push us further still.”

It was that collaborative and outside-the-box design process that Chiang believes made “The Mandalorian” and “The Book of Boba Fett” so successful.

“This is what excites me about designing for ‘The Mandalorian’ universe. It’s always fun, fresh and filled with unexpected surprises,” Chiang concluded. “And when you think about it, that’s exactly what Star Wars design should be.”

Comments